Facts & Trivia

Newly-found fossil suggests that earliest dinosaurs laid soft-shelled eggs

Scientists now have to rethink their preconceived ideas regarding the evolution of dinosaur eggs because according to new findings, eggs from early dinos were more leathery turtle eggs than rigid bird eggs.

In Nature, paleontologists who studied the fossilized embryos from two kinds of dinosaurs, reported that soft shells enclosed the eggs. This is the first time that the scientists have identified soft-shelled dinosaur eggs.

This is an interesting development because paleontologists thought that all dinosaurs had hard, mineralized eggshells for a very long time.

Before a few years ago, “people thought that everything that’s soft and squishy decays away immediately post mortem,” says study author Jasmina Wiemann, a paleontologist at Yale University. However, there is growing evidence that this organic material can fossilize. Certain environments can provide the right conditions to preserve soft tissues, she says.

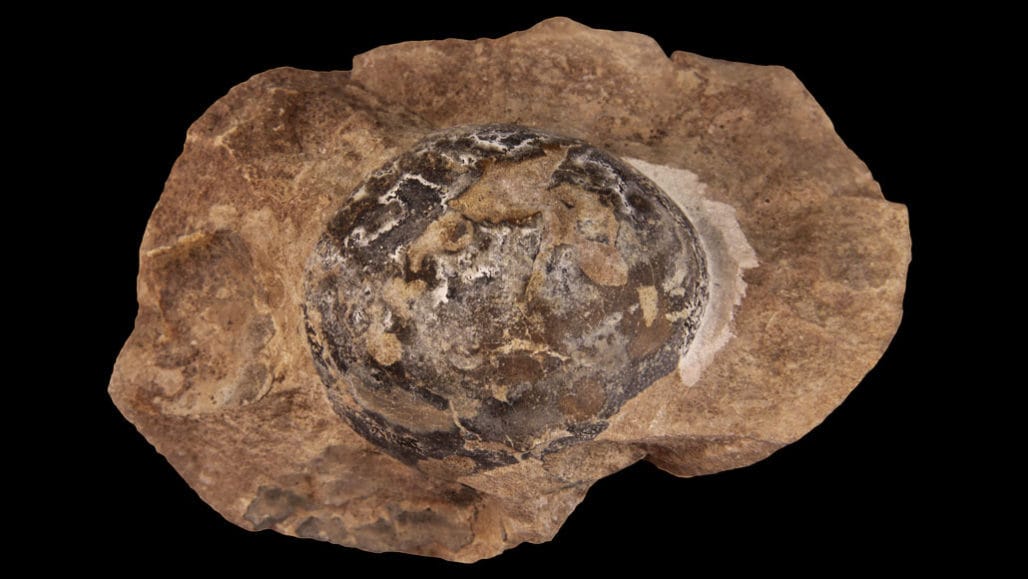

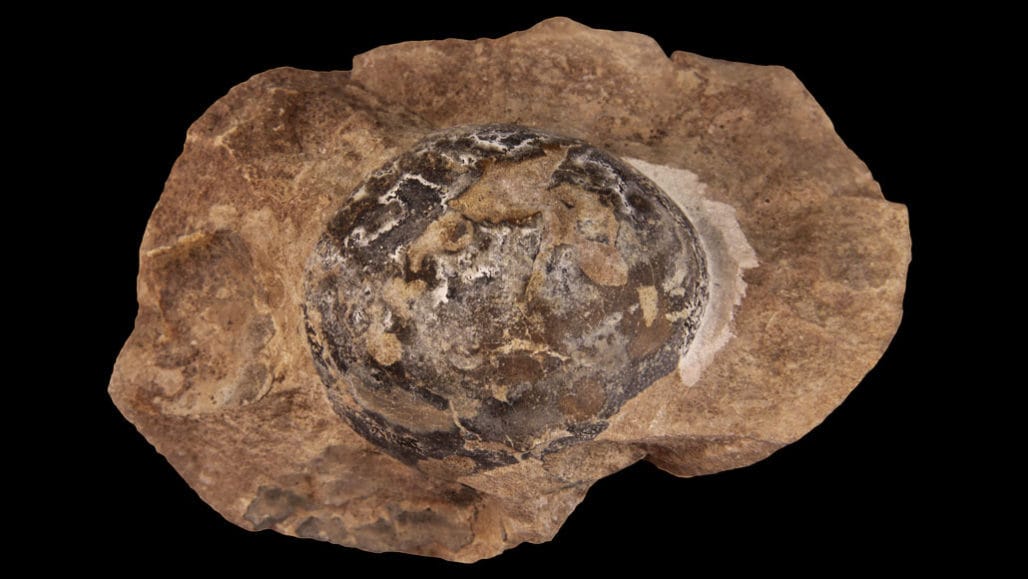

In their research, the paleontologists analyzed a clutch of dinosaur eggs unearthed in Mongolia and dating to between 72 million and 84 million years ago. The collection is attributed to Protoceratops, a sheep-sized ornithischian. The team also analyzed another egg, found in Argentina and dating to between 209 million and 227 million years ago. It was attributed to Mussaurus, a sauropod ancestor.

Studying the dinosaur eggs weren’t easy because the soft eggshells are tricky to spot.

“When they are preserved, they’d only be preserved as films,” says study author Mark Norell, a paleontologist at the American Museum of Natural History in New York City. When examining the fossilized embryos of both kinds of dinosaurs, the researchers noticed the diffuse egg-shaped halos around the skeletons. A closer examination of the halos revealed thin brown layers. The uneven arrangement of these layers suggested the material was organic, or carbon-based, rather than mineralized.

The team also used Raman spectroscopy to study the chemical composition of the proposed soft shells. This nondestructive technique shines a laser on a sample, and the properties of the scattered light indicate what kind of molecules are present in the shells. Wiemann had used this method before in identifying the pigments in dinosaur eggs

The researchers then compared the chemical fingerprints of the fossilized eggs with the fingerprints of fossilized hard-shelled dinosaur eggs, as well as eggs from present-day animals. The Protoceratops and Mussaurus eggs were most similar to modern soft-shelled eggs.

Combining this and other eggshell data with the evolutionary relationships of extinct and living egg-laying animals, the researchers calculated the most likely scenario for dinosaur egg evolution. They determined that early dinosaurs had soft-shelled eggs and that hard shells evolved multiple times in dinosaurs — at least once in each major lineage.

These findings suggest it will be important to revisit past conclusions about dinosaur reproductive behavior, which primarily relied on analyses of theropod fossils. For example, oviraptorosaurs sat on eggs in open nests, like modern birds. But such behavior may not reflect general dinosaur practices because dinosaur eggs evolved independently, what researchers have deduced about parental care may represent just one lineage, Wiemann says.

“If you have a soft-shelled egg,” Norell says, “you’re burying your eggs: [there’s] not going to be a lot of parental care. It makes the dinosaurs of that soft-shelled egg more primitive reptilian than birdlike in many ways.”

Now that paleontologists know what to look for, the search is on for more soft-shelled dinosaur eggs. “I would not be surprised if other people come forward with other specimens,” says Gregory Erickson, a paleontologist at Florida State University in Tallahassee.

Source: www.sciencenews.org